The new multi-breed genetic evaluation with the American Simmental Association has been a fairly smooth transition from a data and EPD perspective. Coupled with the database move to Digital Beef, there’s been a lot to digest in the last 12 months. Breeders have done a tremendous job of adopting and understanding the new breed averages and variation versus the old system. Likewise, your dedication to seeing that genomics is a tool in the box for all Shorthorn breeders has been incredible. On the other hand, much to our disappointment, the genomics ‘train’ has been an extremely slow ride with a number of stops, delays, and outright frustrations. Rest assured, the train is still on the tracks and headed in the right direction, albeit at a sluggish pace. This article should help prepare you for when the genomics train finally reaches the station. As well, it will offer insight for when utilizing genomics is a good idea versus other genetic selection tools already in your arsenal.

First of all, it is extremely important breeders understand genomic tests are not the ‘golden egg’ to beef production, maybe just the shiniest one of the dozen. Likewise, genomics cannot replace the need for collecting performance and carcass information on your herd. In reality, data submission is more important than ever to ensure that the money you invest in a genomic test is worth the spend. Like every other column on the paper, a genomic score is only as good as the data behind it, or in front of it (chronologically) in this case. Genomic tests are generated by taking information from higher accuracy animals, then using it to help predict the performance of young, low accuracy animals. As a result, genomics can only enhance the traits we already collect. For example, Shorthorn breeders will not be able to pull a hair or blood sample to enhance udder quality or docility until an EPD for those traits exists.

Which animals in my herd do I test? When do I collect and submit the samples?

In developing the tests, we asked for semen and/or DNA samples on older A.I. sires. Moving forward, there will be no reason to dig in the tank and test old genetics. Genomics cannot help the EPDs of high accuracy animals; they were used as the baseline for comparison to get the breed started towards genomic-enhanced EPDs. The true value of genomics is enhancing young animals not yet old enough to generate progeny, particularly daughters in production. Under the current system, a sire is 4-5 years old before performance data from his daughters can affect his EPD profile. A genomic test can fast forward some traits on the paper as if the bull already has 15 daughters in production! Young bulls or heifers that show promise can be tested as young as 1 month of age. If pulling hair, be sure that the root follicles or “root bulbs” come out with the hair strand. A blood sample may be better for extremely young cattle. Results from the genomic test may help breeders make decisions on how to manage or market that individual.

Many breeders collect DNA samples for genomic testing at either weaning or yearling. The cattle are in the chute, making the collection of hair or blood a part of the routine. Decisions can be made at a later date as to which animals actually get submitted; no need to submit DNA on critters headed to the cull pen or feedlot. In contrast, samples need to be submitted well in advance of printed sale catalogs. For example, if your bulls or females sell in March, submit the DNA in the fall so results enter the genetic evaluation and enhance the EPDs that typically come out in January.

What could I learn from the genomic information?

The days of stars and 1-10 scores for individual traits are gone. All genomic results are incorporated into the EPDs of the individual. It is important to note that genomics cannot “enhance” every trait on the paper equally. Unfortunately, some traits are largely controlled by the environment the calf endures; others are much more controlled by genetics. For example, the sex of the calf and the color of the hide are 100% controlled by genetics. No matter what we do to that animal from a management standpoint will not change the sex or the color of the calf at birth. On the other hand, a trait like Maternal Calving Ease EPD has a huge environmental component. How we feed, breed, and manage that cow can largely affect her ability to calve. However, genomics can play a significant role in this trait by offering genetic insight to the likelihood that a bull’s daughter will calve on their own. In a nutshell, the harder the trait is to measure, the more important genomics can become at enhancing the EPD.

Genomics also somewhat rely on the heritability of a trait. Heritability is the measure from 0 to 1 used to describe the level of genetic influence on the trait versus environment. Some look at heritability like a percentage of the phenotype that is ‘inherited’ by genetics. The higher the number, the more genetics influence the result. Marbling is a unique trait where genomics has been successful. Heritability for marbling is considered moderately heritable at approximately 0.30-0.35 for most breeds. A few small segments of the genome in some breeds do a very good job of predicting marbling, so the genomic test is successful. Other traits like Scrotal Circumference have very low heritability (0.10-0.15). If a genomic test can find markers that have a large influence on scrotal circumference, then the test has value. However, if scrotal circumference is truly controlled by thousands of gene segments, then the likelihood a genomic test is useful is very low. Breed to breed, genomics may show real promise for a trait in one breed, but be virtually useless in another breed. As a result, breed associations must independently develop and validate their own genomic tests.

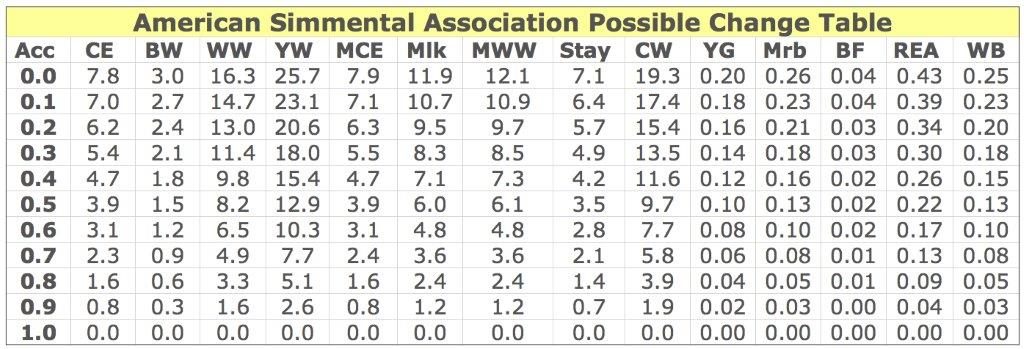

Please don’t let the chart below overwhelm you; it can be very useful in understanding the effect genomics can have on an EPD. The Accuracy from 0 to 1 is down the left side. Individual EPDs are across the top. Keep in mind that some columns are not Shorthorn EPDs…yet. Most all pedigree estimate EPDs (the average of the sire and dam’s EPDs) come in under 0.10 Accuracy. Obviously, if the breeder reports calving ease, birth, weaning, and yearling data on the bull, the Accuracy for the bull’s growth traits can go up to roughly 0.35. Let’s use BW as an example.  If you buy a yearling bull that is a +2.0 on BW EPD and his Accuracy is 0.10, the chart tells us that 68% of the time (1 standard deviation) the bull’s “true” EPD for BW will be between -0.7 and 4.7. And yes, 32% of the time, his true EPD could be even worse…or even better than that.

If you buy a yearling bull that is a +2.0 on BW EPD and his Accuracy is 0.10, the chart tells us that 68% of the time (1 standard deviation) the bull’s “true” EPD for BW will be between -0.7 and 4.7. And yes, 32% of the time, his true EPD could be even worse…or even better than that.

If the Shorthorn genomic test is run on that bull, his BW EPD may be +2.5 with an Accuracy of .40. Now, refer to the chart. The bull is now plus or minus 1.8, making his EPD likely between +0.7 and +4.3. We gain confidence that the bull is likely not a candidate for heifers. I would encourage you to enter the following link in your browser and read Dr. Scott Greiner’s article that further explains the chart.

https://www.herdbook.org/simmapp/action/pages.PagesAction/eventSubmit_displayPage/T/pageId/15/

Given our relatively small sample size, genomics for the Shorthorn breed will be an ongoing commitment from breeders of all sizes. The more performance data that gets submitted, the better the genomic tests can become. As an example, if we find a “rock star” bull for Marbling EPD based on ultrasound and the genomic test, we still need to follow his progeny to the rail and collect marbling scores or at least scan his sons and daughters to prove the bull even further. Then, we revalidate the genomic test for Marbling EPD and it becomes even more powerful and more significant as a tool for selection. In the end, genomics can be a real asset to breeders with just a few cows, those that rely heavily on embryo transfer, or breeders with large contemporary groups as they try to find ‘the one’ that will give them an edge or move their herd forward at an accelerated pace. The train is comin’.

Written By: American Shorthorn Association contributor, Patrick Wall

Patrick can be reached at patwall@iastate.edu